The Brutal Truth

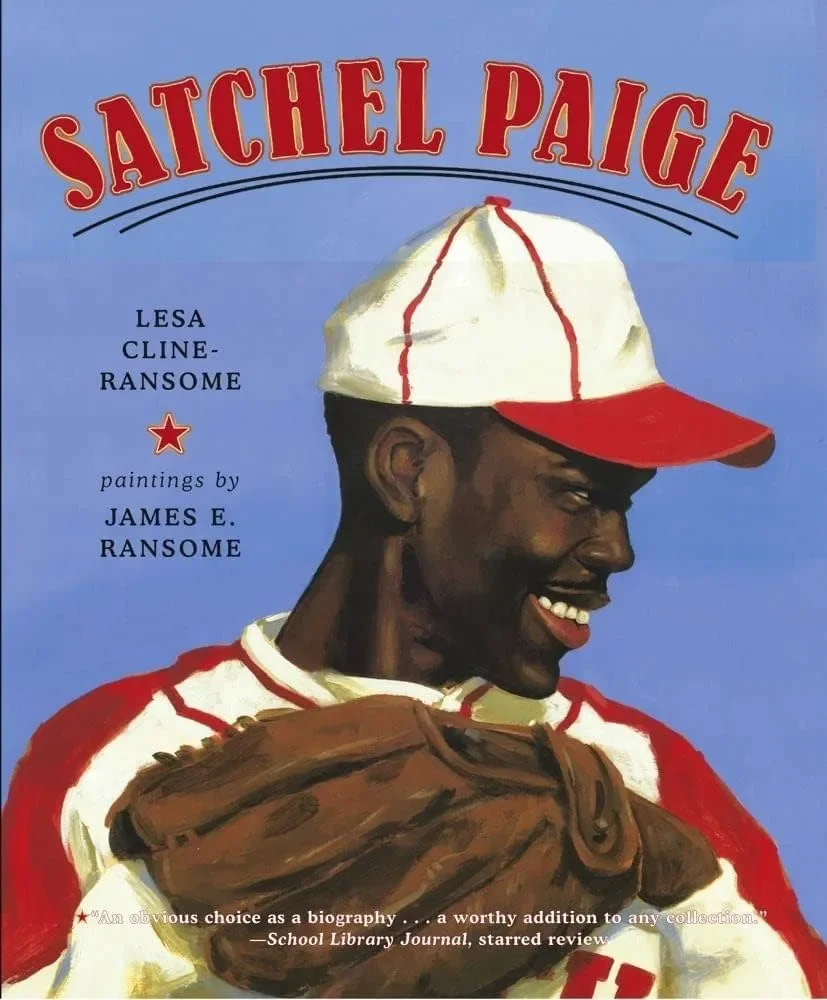

I began my writing career by publishing a picture book biography of the Negro League pitcher Satchel Paige. He was an iconic figure who brought to baseball a unique blend of sportsmanship and showmanship. In a team sport, he was a loner, forgoing the team bus to drive alone in his own car to games on the road. Some games, he wouldn’t bother to show up at all. Instead of sharing the spotlight, he sought out the limelight. Asked his age, he gave interviewers various ages that spanned nearly twenty years. His own autobiography provided a fictional birth date.

As a new writer, I struggled to find a way to balance the complexity of a man so talented in one area in his life, but so personally flawed in others. Satchel Paige was called larger than life, a character, a storyteller, but he wasn’t often called what he was—a man who also lied. I worried, Is this something that I can tell young readers?

Just last month, I completed my first long-form nonfiction biography that extended well past one deadline and several more. I spent too much time fussing over pre-writing strategies I’d never fussed over in my pantser past—what the structure should be, how many chapters it would have, chapter headings. I wasn’t sure exactly how to tell the story of a woman whose life couldn’t be confined within chapters, headlines and outlines.

Ida B. Wells was a journalist, activist, suffragist and anti-lynching crusader. She was born in 1862 six months before the Emancipation Proclamation, just shy of freedom. She and her five younger siblings were educated at a Freedman’s Bureau school in her hometown of Holly Springs, Mississippi. Her mother Lizzie attended school with her children, hoping that learning to read and write would help her to correspond with newspapers as she sought to reunite with family members that were sold off during enslavement.

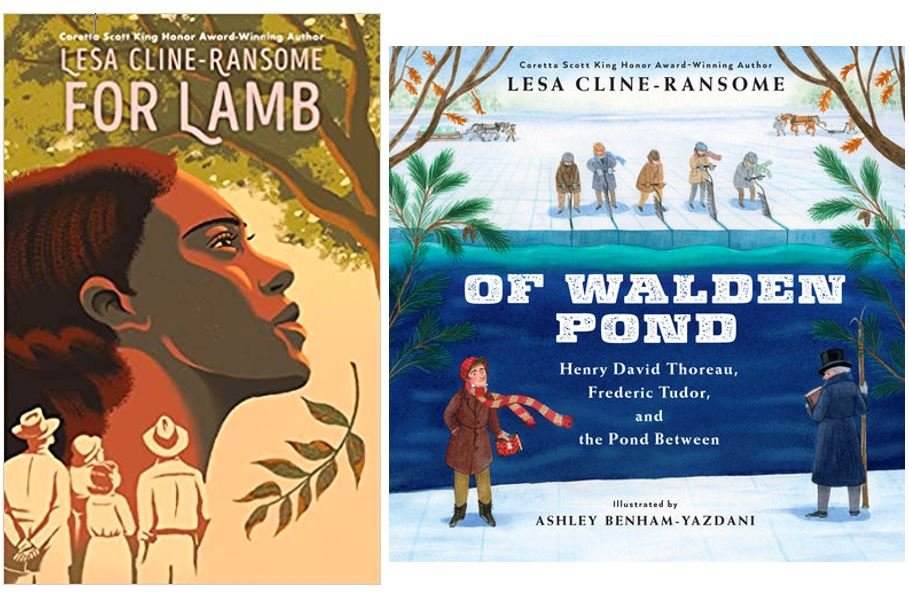

As a young girl, I had seen the name Ida B. Wells among the many black history heroes listed in the Jet and Ebony magazines that were a mainstay in my home. But I came to understand the impact of her legacy most fully through research for my first young adult novel, For Lamb.

For Lamb explores a secret interracial friendship between two teenage girls in the Jim Crow South and the deadly consequences of their actions. Much of my research focused on the female victims of lynching. Ida B. Wells’ The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States became one of my most valued resources as I looked at the numbers of black people lynched following Reconstruction and throughout the decades that followed. It was in no small part, due to Ida’s advocacy and spotlight, through her endless investigations, editorials, speeches, boycotts, and demands for justice that political leaders, newspapers, that the nation finally began to pay attention to the atrocities being committed on its black citizens.

“The way to right wrongs is to shine the light of truth upon them,” Ida once wrote, and shine the truth she did. In her early thirties, she was the first black woman to own a national newspaper. And the editorials she wrote for the Memphis Free Speech sparked fury among the city’s white citizens.

“Nobody in this section believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men assault white women…” she wrote in an 1892 editorial entitled “The Brutal Truth.” Several days after its publication, while Ida was visiting New York, the Free Speech offices were destroyed. A white mob stood stationed at the train depot awaiting her return intent on killing her.

Ida B. Wells —Original: Mary Garrity Restored by Adam Cuerden

But it would take more than the destruction of a printing press to silence Ida. She didn’t return to Memphis but she did continue to publish her scathing editorials lambasting cowardly politicians, religious leaders and a two tiered justice system—one for whites that included a fair trial and one for blacks that needed only an accusation to render judgement by a lynch mob.

Unlike Satchel Paige, Ida was a teammate to her entire race. She spent much of her life embattled, questioned at every turn for the decisions she made. Sometimes with those in her own race who felt she was too outspoken; sometimes with other women activists who questioned her dedication to the cause when she married and became a mother. She waged war with Frances Willard, the white Christian Temperance president and longtime abolitionist who, in an interview, blamed the lynching of black men on their drinking and illicit behavior. She called out the white press for their biased reporting, allowing their headlines to scream out unfounded accusations that offered cover for mob behavior. Although she was just over five feet tall and petite, she physically fought off a white train conductor and male passengers who attempted to remove her to a 2nd class smoking car when she’d bought a first class ticket. She refused to acquiesce to the will of white suffrage organizers at the 1913 first National Women’s Suffrage Parade who told her to march at the back in a section designated for black suffragists to appease their southern white contingent. Ida stayed put and marched with her own Illinois delegation, the only black woman walking proudly at the front.

What version of the truth do we owe our readers?

Her life’s work it seemed was fighting, but essentially Ida was fighting the lies that sought to define and justify the harming of black people. “Black people are more sinned against than sinning,” she once wrote, and she needed the world to know it.

The facts she uncovered revealed that while black literacy rates soared, black businesses opened, black land ownership increased, so too did the rates of lynching of black citizens. The reasons given for lynching were predicated on a lie—that lynching was used as a tool in the protection of white women from the sexual assault by black men. And here was Ida, with the truth in hand dispelling that narrative with facts and figures. The year her Red Record was published, accusations of rape or attempted rape accounted for a mere forty-seven of the one hundred and ninety-seven reasons provided for the lynchings that took place in 1893. If rape was the cause, what then could account for the number of black women being lynched, Ida asked.

At a time in our world when the truth feels optional, when lies are repeated as easily as breathing, when the people who spout them suffer little consequence personally or professionally and can even be elevated to the highest office in the land, as writers, what is our obligation to the truth? What version of the truth do we owe our readers?

Over the span of thirty books and twenty picture book biography subjects, and in the years and missed deadlines it has taken me to absorb the life, work and legacy of Ida, what I have learned is that my obligation is to offer an honest accounting of a life or “The brutal truth,” as Ida described it.

The world of nonfiction is a world of truth telling. But how much is too much is a question I have been grappling with since I first sat down to write Satchel Paige.

When I think of Ida and her battles and her steadfast grip on honesty, I looked at anti-lynching resolutions passed in state after state. The victims she memorialized by giving them voices and names. And I thought of a country that was finally forced to face its own shame through the hard honest work of Ida and others—Frederick Douglass, Mamie Till, the NAACP—and it was only then the lynching slowed to a stop.

We are entering a moment when honesty about real life experiences, history, and injustice can come at a cost, especially for writers in marginalized communities in the form of censorship and banning. And just maybe we can’t all be as brave as Ida, or morally courageous as the heroes we read and write about, but don’t we owe it to ourselves and our readers to at least try?

In community,

Lesa

My forthcoming book, "Ida B. Wells: The Untold Truth of a Country" releases September 2026 (Holiday House)

Letters from Home

Photo by rc.xyz NFT gallery on Unsplash

Dear Lesa,…

The letter from my mother arrived as it always did, to my dormitory mailbox at 200 Willoughby Avenue in Brooklyn, New York. I had been aching to live in New York ever since middle school and the series Welcome Back Kotter aired on tv and Saturday Night Fever hit theaters. The grit, and lack of pretense of New Yorkers spoke to me. I imagined that I’d be gloriously at home surrounded by tenement buildings, graffiti and Brooklyn accents stronger than my Boston one.

But when my parents drove away from the Pratt Institute parking lot, I realized I already missed home. Missed it so much that I called my parents three times a day from the lobby payphone.

Within my mother’s weekly letters were pieces of home—the daily errands she ran, what she and my father ate for dinner. Nothing revelatory, but I’d save them in piles in my drawer and reread them as needed, when I was at my most homesick, feeling as if I’d lost my moorings.

I have begun again to write letters at a time when manual writing is becoming obsolete. Elementary schools have ceased teaching what was once a staple of my grade school curriculum—penmanship and cursive writing. Who needs penmanship when we no longer write by hand?

Teachers bemoan the fact that their students can no longer decipher the cursive writing in documents like the Declaration of Independence, let alone sign their own names.

When my siblings and I recently sold our family home after the death of my mother, it required us to do the much put off task of clearing out the house. We trekked upstairs to a stifling attic where boxes and crates, ancient issues of Ebony, Jet, and Boxing magazines were piled. My brother discovered his first toy chest, I grabbed albums from my father’s vinyl collection. And then, as we turned to head downstairs for a break my brother said,

“Lesa, you’ll want this.”

It was a diary. My mother’s 5-Year Diary from 1942-1947. She was sixteen years old when her diary entries began and in those pages, I traced her life living in Everett, Massachusetts with her parents Anne and Elbert Sneed, and her four younger siblings, twins Elbert and Elvera, Lewis and Shirley (her youngest sister Ruby had not yet been born.) and several children that my grandparents raised as their own.

January 3, 1942: There was house cleaning today and plenty of baths. I got a letter from Raleigh (her uncle) and a picture from Dalton Smith.

I never knew my mother kept a diary. But maybe I should have guessed it. She was a woman who kept secrets close and respected the privacy of others. When I was 10 years old, I returned home from school to discover that my mother had bought me my own diary, complete with lock and key. The cover was a blue floral pattern and inside I quickly inscribed my name in my once neat handwriting under the lines “This Diary belongs to…”.

I shared a room with my seven-years-older sister Linda. In our room, nothing was completely mine. She decorated, decided when we slept (after she finished her late-night phone chats and playing loud music). She spread her cosmetics and fragrances across “her” dresser. But the diary my mother gave me was all mine.

Long after my diary writing ceased and I left for college, the diary lay untouched, hiding in the bottom of the dresser I’d claimed when my sister left for college. I don’t know where the diary has since disappeared to. Most likely it was among the many attic items I wasn’t able to rescue. But I remember how important that diary was to my private and writing life. I finally had a place to vent my frustrations and insecurities to craft stories from my childhood adventures with friends. I could yell at my sister without actually yelling at my sister.

My mother’s diary involves no yelling. She documents her teenaged life in a manner that was so starkly different from my own—dance lessons in her living room, ice skating, bowling, church choir practice and reading. I wondered when and where she had time to write her private thoughts in a home filled with family.

When I read the entries in her signature handwriting, I am reminded of her letters from home and the cards she sent for every birthday, every holiday, every heartache.

April 23, 1942: I went to see Count Basie and Maxine Sullivan tonight…

Some argue that communicating electronically is the new shorthand. But what of the distinction of handwriting, the idiosyncratic flourishes that are part of written correspondence? While we text and email and post on social media with regularity, nearly sixty-four percent of the population report that they will never write a letter by hand.

Historically letter and diary writing has been the realm of many white men and wealthy white women. There are only four published diary accounts of black women from the 19th century—journalist Ida B. Wells, educator Charlotte Forten Grimke, poet Alice Dunbar Nelson, and seamstress Emilie Davis.

Alice Dunbar Nelson — Unknown Photographer

Research for so many of my historical nonfiction and fictional narratives involve digging through primary sources to extract the vital stories of my subjects but there are far fewer primary source documents and photographic evidence from people of color. They continue to be left out of history. The lives of black people were rich and diverse and complex, and yet, too many of their stories have been written and narrated by others.

I often wonder how much harder researching will become when so much of our correspondence is relegated to the digital world? When our handwritten letters, notes and diaries disappear from our archives.

My once uniform print has evolved into scraggly, barely legible markings, but I have returned to letter writing because what I know is that no text message could ever replace the intimacy of the written word. My handwriting and the ways I which I communicate with paper and pen are my own indelible imprint. From the stationery to the fold of the paper, to the color of the ink, those elements become part of the message.

Our writing need not rival those of Martin Luther King’s letters from a Birmingham jail or Thoreau’s journal meditations on the natural world. Quotidian writing holds every bit as much relevance in documenting the truth of our lives.

Write a letter. Send a postcard. Make notes in a journal. Sharpen your pencil and know that in writing with your own hand you are preserving the story and the history of you.

In community,

Lesa

From Fear to Freedom

On a cold Sunday night in late January, I received a call from an unidentified number.

“Is this Lesa Cline-Ransome?” the voice on the other end asked.

I was sitting in a parking lot—a very dark parking lot—waiting for a takeout order while calculating on my phone the measurements for wallpaper. Yes, wallpaper. I was three weeks into a kitchen and bathroom renovation, and well… wallpaper calculations can be tricky. So, as I added the wall dimensions again and again to determine how much would be needed for a tiny bathroom, I was also calculating the cost of wallpaper for a tiny bathroom. Why does the cost of wallpaper equal the cost of a monthly mortgage payment? I wondered.

What I wasn’t doing was expecting a call.

“This is Lesa,” I replied suspiciously.

“I am calling from the John Newbery Award committee to congratulate you on winning…”

Math has never been my strong suit, but this definitely did not add up.

“Is this real?” I asked the caller. The caller assured me that it was indeed real. I heard a group of people cheering in the background.

“Congratulations!” they shouted.

My breathing stopped. I began sweating. I felt dizzy. I know all of the things I should have said, was supposed to say, but instead I replied, “I think I might be having a stroke.”

It was late. I was in a parking lot. This was not how a call telling me I’d won a big award was supposed to happen.

What made this call so shocking was that earlier in the day I’d received another call. Well, it was actually several calls from the Coretta Scott King committee. Did I know that my phone settings were on Do Not Disturb? Nope. And so as they repeatedly tried to reach me on my cell that was across the room, silenced, they received my voicemail instead.

I finally noticed the missed calls and a text message that read “The Coretta Scott King Book Awards Jury has some exciting news to share with you. We will try to reach out again…”

Instead of answering a call from the committee, I had to make a call to the committee to receive the news that my first novel in verse, One Big Open Sky had won a Coretta Scott King Author Honor. I believed then that the day could not get any better. Until it did.

I have loved verse novels ever since reading Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse decades ago. The way the novel addressed themes of nature and survival, community and hardship and the enduring power of forgiveness in spare, free verse poetry changed the way I viewed poetry as a narrative form. Years later it was Sharon Creech’s Love that Dog that taught me how poetry can so perfectly capture the vulnerability and tenderness of young characters. And, of course, it was also a book about the love of a DOG. Any title that is centered on the best species on the planet is a win for me. If you don’t agree, go kick rocks.

Alan Wolf took a slice from a tragic story in history and transformed it into moments of beauty and grace in his free verse novel The Snow Fell Three Graves Deep: Voices from the Donner Party. And in Jeannine Atkins’ Borrowed Names: Poems about Laura Ingalls Wilder, Madam C. J. Walker, Marie Curie and Their Daughters, I discovered the power and complexity of interwoven family stories.

With these verse novels and so many others under my literary belt, I began my journey into writing verse, diving deep into the history of Black Pioneers, Exodusters they were called, and the stories of women traveling overland in the 1870’s.

Thousands of Black people emigrated West along the Santa Fe, California and Oregon trails with the hope of land ownership on the tribal lands stolen from Native Americans. The Homestead Act of 1862 offered 160 acres of this “free” land for any citizen willing to cultivate, plant and build a structure within five years.

All black people have ever known was hard work, and this land represented the chance to escape the sharecropping system, build a better life for their families and create a safe community thousands of miles from the Jim Crow South. From fear to freedom they made their way West, battling discrimination, nature, and limited supplies. But it was the stories of the women, powerless in the decision to stay or leave, whose voices came to me in verse. Their stories were ones of remembrance, longing for the past, fear, and perseverance. Many were pregnant along the journey, many lost young children to accidents, husbands, fathers and brothers to shooting accidents and drowning, and so they only had each other to rely upon. Sisterhood is what saw them through.

…I asked Lettie to take the boys

berry hunting

Wasn’t so much needing berries

as much as I was needing

time with Dottie and Clara

to make some part of me

whole again

Every day we travel

the hurt of leaving Olivia

and my brothers

felt like leaving pieces of me

along the trail

I worry by the time we reach Nebraska

There won’t be much left

Sylvia, Missouri

June 1879

(Excerpt from One Big Open Sky)

Poetry provides an access point in revealing both the hard truths of this country and how we emerged with our hearts and souls intact.

In One Big Open Sky, 11-year-old Lettie is the peacekeeper who is straddling the expanse between the sadness of her mother Sylvia and the dreams of her father Thomas.

Throughout the writing of this novel, I often felt much like the pioneers had, lost and fatigued, unsure if I should keep going or turn back. I questioned nearly every writing decision I made, every line break. I wondered daily, “Can I do this?”

I imagined those brave women pioneers and my characters Lettie, Sylvia, and Philomena, unsure of the road ahead.

The wonderful calls I received at the end of January felt like a guidepost, telling me to keep going. Keep trying new ways of storytelling.

Since that cold day in January, I have replayed those awards calls numerous times. Sometimes I still wonder if they happened at all. It is hard to believe that a story, my story, about Black pioneers was recognized in this way. Especially with all of my fears and doubts and all of the incredible books that came into the world in 2024.

But in June, I will head to the American Library Association conference in Philadelphia, and if this all isn’t a horrible practical joke, I will return back home to a renovated kitchen, a gorgeously wallpapered bathroom, and two very real awards telling the story of two difficult journeys.

In community,

Lesa

Making Time for a Life of Writing

Photo by Ella Jardim on Unsplash

It is taking me longer to write books these days. For no particular reason other than it is taking me longer to write books these days. I once imagined that as my children grew larger and my nest grew emptier that my work days would grow proportionately longer.

But, much like a newly cleaned out closet, what was once empty mysteriously and incrementally refills.

In the space left behind by my children, I now find myself sitting at my desk doing everything but writing—sending emails, scheduling appointments and events, chatting on Zoom meetings and interviews, reading, organizing my calendar, booking travel, preparing talks and presentations, composing social media posts, daydreaming, and trying and failing to avoid the daily news doomscrolling. Of course there is much grumbling about all I need to do to first clear my head and my desk before my mind can settle on the task of writing. Meanwhile the clock ticks and the hours disappear.

When I meet other writers who seemingly manage to get a lot done in their day, I quiz them—“What time do you get up each morning?” ”Do you find time to read?” “Do you cook?” What I really want to know is, Can you truly have a full and productive life and do all the things that come with being a full time writer?

What am I feeding? Everything but my writing. The tasks that require the least of me.

Once upon a time, at the start of my writing career, my days were packed with the making of school lunches, kid drop-offs and pickups, homework help, sports practices, and playdates, dinner making, doctor’s appointments, rinse and repeat. My writing was tucked in the in-between times, scratched out in the notebooks I toted to and fro.

Often those notebooks were crumpled messes and a diary of life on the go, smudged with yogurt and lipstick, and in the margins of the pages, scribbles of other appointments I needed to keep. I counted myself as a time thief—stealing and sneaking scraps of time away as if they weren’t truly mine to own.

And if I didn’t get the balance just right, if I “stole” or “borrowed” too much from one part of my life, the other parts would feel the shortage. No dinner again tonight? Did you buy the supplies for my project—it is due today! I would apologetically return some of that borrowed time to its rightful owner while my writing sat again unattended, waiting.

My children, having flown the proverbial nest, still have phones that can reach me at all times of the day with grave emergencies. “I’m bored,” one calls to report working from their remote job. Another asks, “What should I have for lunch?” “Should I go see a doctor about…” Meanwhile, the clock ticks and the hours disappear.

“Everyone has a to do list,” says writer Anne Lamott, “Today cross two things off of your list and spend that time writing.”

I have tried Lamott’s methods and many others—color-coded calendars, time blocking, timers, and daily word counts, all with mixed results. I plan my day, hoping that what is on my calendar will translate into some version of sentences or research or even notes on a page.

I begin each day with the promise of accessing more of what wasn’t there the day before. I think of what my writing day will yield each as I do my morning stretches. When I head out on my walk I plan what I will first work on, seeing in my mind’s eye the sentences form. In the shower, I speak to the characters I’ll shortly be visiting. But by the time I descend the stairs and make my way into my office and sit at my desk to begin, I open my inbox and… the clock ticks and another hour disappears.

One recent morning I tried a new guided meditation where the mantra was “What you feed grows.”

What was I feeding? I asked myself, vowing to tuck away that morsel.

I returned to my desk and began my day—Sending emails, scheduling appointments and events, zoom meetings, interviews, reading, organizing my calendar, planning trav—….wait…Is this what I am feeding?

Even with all of the time in the world, I am beginning to recognize that what is sitting before me is not a lack of time. There is nothing that any of my time management books can cure.

What am I feeding? Everything but my writing. The tasks that require the least of me.

The work of writing requires not only time and daily attention but intention. An understanding of the who you are writing about and the why you are writing. It requires the very hard work of committing words to a page. By feeding my to-do list first, the less time I am devoting to feeding my own writing.

Yes, I am busy. And yes, my day is full. Those facts aren’t likely to change anytime soon. But could it also be that I have more than enough time? That what I need more than extra hours in a day is the strength to embrace the time I have and the courage to put aside all else, face the fear of of a blank page and write?

In community,

Lesa

January 2024: Revision Reflections

Photo by BoliviaInteligente on Unsplash

I love a New Year. Because with the New Year comes my hope for a new beginning. It’s not as if the past year has been one filled with gloom and doom, but there is something about a new year that promises 365 days of something much better than whatever the last year held. It’s like a bright Monday morning when the week is just beginning, your energy level is high, and your long to-do list seems actually doable. Or the first day of school when you’re wearing shiny new shoes and you just know that your hard work will yield straight A’s on each and every report card.

For most of us, All Is Possible at the stroke of midnight at the start of a new year. Weight will be lost. Money will be saved. And finally, at long last, the novel you’ve been putting off for so long Will be written. For me, not a year begins without the hope that This Will Be the Year I will achieve ALL of my professional goals. I will write five award-winning books. I will meet all of my deadlines. I will find time between writing my award-winning books to Travel, Cook Amazing Meals for Friends and Family, Garden and Exercise Daily. Perhaps I will even write a Travel Cookbook Memoir (with recipes from my garden bounty)! I will keep a clean and organized desk to meet my deadlines and write my books. And when not writing, gardening, or cooking, I will read every single book on my TBR list. Not such a tall order for the start of a new year, right? Because it’s 2024 and Anything Is Possible!

And that is precisely where I get myself into trouble.

It could be the month of January that is partly to blame. Here on the east coast, gray skies, short days, and cold air in a very long, nearly holiday-free stretch make January the bleakest of months. Wedged between merry-making December and a romance-themed February, January seems downright depressing. If it weren’t for the New Year goal-setting (and, of course, the celebration of MLK Day), what else would January have to offer?

Yet the unrealistic goals I place on myself as a writer at the start of the new year have led me to my annual end-of-the-year doldrums. How is it that I missed so many deadlines? My ingenious book ideas sit in files waiting to be written. Unread stacks of books seem to only grow in piles around my home.

Generally speaking, resolutions are a fail.

They fail for the same reason that gym memberships dramatically increase in January and dramatically decrease by February. Routines, not resolutions, are what keeps you going long after willpower fades. It is the daily work of showing up that matters, sometimes more than the final results. If I know this, why then does my off-the-chart, unrealistic goal-making continue year after year?

Perhaps it is because this is what writers do. Dream up worlds. In this case, a purely fictional world where I am the protagonist acting out the part of the hyper-focused, flawless writer I myself have never met.

As any writer knows, the work of writing is never about one month on a calendar. It is about all twelve. It is about the act of sitting in your chair with your head in your hands, wondering when the words will come and thanking the universe when they do. And the next day doing it all over again with hopefully slightly better results.

Routines, not resolutions, are what keeps you going long after willpower fades.

Goals. Resolutions. Both are perfectly fine. But if you really want to stay committed to writing in 2024 and beyond, consider a few more practical offerings I have gathered from some writing folks through the years:

First, spend time thinking about what you want to write and WHY? Understanding your writing goals is crucial to how you approach everything from the time you devote to writing, to managing a career, to choosing the subjects on which you will focus.

Find community. No one keeps you more on track and motivated than a group of other writers to whom you are obligated to share pages and progress, engage with their writing and yours, and give and receive critical feedback. Both in-person and virtual writing groups are available at Jamie Attenberg’s #1000wordsofsummer, #nanowritmo, #12x12writingchallenge, along with other orgs for writers like SCBWI.

Develop a routine that works for you. An hour each evening, voice recordings during your morning walks, writing on your lunch breaks—whenever it is, set aside time on days you decide and be consistent by showing up for your writing.

Write for yourself. Not all writing is meant for publication. Some writing, like journaling, is more about tapping your creativity and/or understanding yourself. You get to decide who your audience is. Or, in the words of novelist Sam Lipsyte, “Don’t think about a career. Just think about the next sentence.”

Do find time for something other than writing. Like gardening, traveling, walking, dancing, cooking. Each experience enriches your writing journey.

Cheer yourself on when your goals are met, but especially when they aren’t. Writing can be a long, tedious journey, and you’ll need to learn to be your own best friend, cheerleader, and advocate.

Happy 2024! Here’s to a new year of simply beginning.

In community,

Lesa

Revision Refections

Photo by Max Saeling on Unsplash

I have learned the hard way that writers spend much of their time waiting. Anxiously awaiting replies to submissions and queries. Nervously waiting for advances and royalty payments. Waiting for someone, anyone, to walk through the door to sit in an empty chair at a book event. Gather any group of writers in a room and conversations center around who is in what stage of waiting. “Just waiting to hear back from…” “I sent it in two months ago and I’m still waiting…” “How much longer should I wait before I…”

To be a writer is to be impatiently patient.

I never imagined that being the youngest child of three would be all the preparation I’d need for life as a full-time writer, where waiting is a job requirement. Being the youngest meant getting used to hearing, “Not yet,” over and over again as I watched my older siblings race off to lessons and practices. I waited for them to arrive home from school. And even after school began for me, it seemed it would be a lifetime before I would enter their intriguing worlds of science experiments, research projects, Spanish classes? Would I ever be big enough, tall enough, fast enough, smart enough? After a while, I resigned myself to the waiting, yet I still bristled with the slow pace of prolonged postponement.

After publishing my first book, and then my second, and then twenty more, I found the intensity of my writing kept pace with my publishing schedule. But so did my fatigue. When I was awarded a residency this summer, I looked forward to the time away, three weeks all on my own, without distraction, to create in solitude.

I’d just experienced a tremendous loss, and for the first time in years, my work had faltered in my overwhelming grief. Healing was needed. Yet the projects were long overdue and I knew that more than anything I needed this time to catch up and deliver. But at the same time, I needed to stop and breathe. How could I do both? Slow down and speed up?

As I arrived at my assigned studio there was a guest book propped on the mantle, its pages filled with words of wisdom from the studio’s previous residents.

Blankness filled me. I had no wisdom, no sage advice, nothing to add to these pages. I was here to work, to complete projects, not to give advice. But as I sat at the desk in front of a large window overlooking the woods, the words I so desperately needed were nowhere to be found. And so in the quiet of the days that followed, I listened to the radio, the owls at night, the cicadas, the whirr of my fan during stifling heat. I walked, and ate lunches that arrived in a picnic basket at my doorstep promptly each day at noon. In the evenings, during the communal meals with the other fellows, when asked, “How’s your work going?” I answered smiling, “It’s going…”

With no Wi-Fi in my studio, I visited the library after breakfast to begin research on one project, then returned to my studio to write in my journal. I read. I napped. I cried. A lot. After four days and not one word of writing, I began to panic. Was I just wasting time? Frittering away a wonderful opportunity? Was my writing career….gulp…over?

I attended presentations of other fellows, soaking in the creative writing, film, compositions, visual art and poetry fostered by their residencies. Together we drank wine in the evenings. And more wine. I made playlists that we sang along to, someone taught us line dances. I played ping pong, darts, bowled. I pulled a hamstring doing some combination of all of the aforementioned activities.

In between I thought of the characters, the stories I’d come to this residency to write about. I wondered where they were. The fear of the teacher who secretly taught enslaved blacks in the 1800’s under the shade of an oak tree. The courage of a journalist fighting violence with truth and words in 1894. The uncertainty of a black wagon company who were traveling west from Mississippi in 1879. Like a new mother, I worried over their future. Uncertain I could ever help them reach the potential I was certain each story possessed. And I did what I knew best, I waited.

“Certain subjects just need time. You’ve got to wait before you write about them,” writer Joyce Carol Oates once said.

I couldn’t quite let go of the idea of completing all that I intended, but I began to surrender my vision of “productivity.” I reimagined work as not only output, but input as well.

And then one morning, as I picked up my journal to write my daily entry, I found, not just the words for my morning meditative ramblings, but sentences. A start of a story. I put down the journal and moved to a pad of paper, scribbling furiously. By the end of the day, I’d begun writing on my laptop. I created an actual document. I named it and pressed SAVE. A structure for the story appeared and then more ideas formed, so I started a new document and saved that one as well. Each day I returned to my laptop, eagerly greeting the characters and subjects, and the words came, tumbling onto the pages. I could see faces, hear voices. I knew these people and their stories. I had not just any words, but good ones, I felt. The words I’d been waiting for. As if they were sitting quietly, shyly in the corner, biding their time.

Stories can’t be rushed, no matter how quickly we need them. Sometimes we need the quiet, the space to let them find us.

“Drafts sit and wait for us to come home, I believe. At least I’ve never met one that made secret progress while I was gone,” Virginia Euwer Wolff, a dear friend and critique partner once emailed when I complained of too much time spent away from my writing during travel.

In the periods I spent not working, I discovered that sometimes the work of writing is to listen. To play. Sometimes the work is waiting to work. All the moments of not putting pen to paper, of not writing, were the times that stories were forming. It is the gift of what solitude and time and breaks, and retreats can provide.

The stories will find us in the waiting. Turns out I did have words for both my story and to leave behind for the journal on the mantle as well.

Stay tuned for news of our upcoming R(ev)ise and Shine! retreats where we trust you will find community and stories waiting…

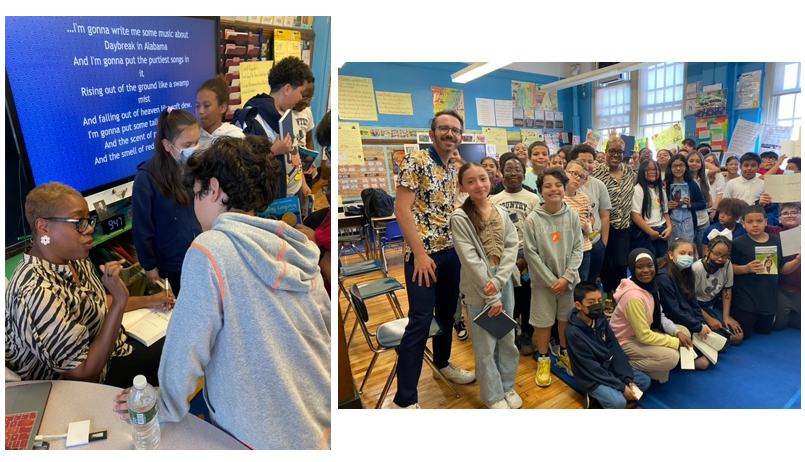

A Bronx Tale: One Teacher's Song

Back to school season is upon us and with it the heightened rush for some, anxiety for others. For me, September is a time of renewal. A season of welcomed change to shake off the laziness of hot summer days, begin anew, dream up new projects, set goals. But it is also the time when I begin once again, to visit schools and students around the country, to talk about the power of story, books and how both can change the way we see ourselves and our world.

Each year I do nearly thirty school visits and by the time the school year ends, no matter how wonderful each visit, how well prepared, how magical the students and teachers and librarians, the fatigue of travel and hotel and being away from home and my routine begins to wear me down. Memorable moments stand out of course--kids brimming with questions, offering me ideas for my next book, sharing their own writing and drawings; impassioned teachers and librarians who go out of their way to make me feel welcome and appreciated; Caring administrators who sit in on presentations, setting literacy examples; and of course, parent and family volunteers who work tirelessly (says the former PTA president!) to bridge the gap between home and school.

But this year, on my very last school visit of the year in early June, tired and worn out by deadlines and juggling, I visited the students at P.S. 96 in the Bronx at the invitation of a teacher named Jake. Jake teaches fifth grade and a short time ago he read my book, Finding Langston, a book he said changed him. So much so, he told me, that he decided he wanted to share the book with his students by using it as grade level read and following it up by hosting the school’s very first school visit. He visited my website, contacted my wonderful booking agent Carmen Oliver at Booking Biz, and asked her to set a date aside. There was only one problem: His school did not have the funding to host an author for a school visit. So, Jake sought out alternative funding and when that failed, Jake took some initiative and started a GoFundMe page. A “Help Me Bring Author Lesa Cline-Ransome to P.S. 96” GoFundMe page to raise the funds for my honorarium.

My agent worked with his budget. Friends donated, his parents, a close pal from Japan, even an aunt he had shared the book with chipped in as well. Jake and the 5th grade students watched as the donations came in and cheered and hoped and somehow, some way, Jake met his goal and raised enough funds to bring me into his school.

Of course, I was unaware of all of this when I visited the school on my very last school visit in June. All I knew was that I was tired, and I was traveling two hours each way from my home in the Hudson Valley, by car, by train, by Uber to the Bronx.

But when I arrived, I was met with classrooms of the most eager students with the most wonderful, the most thoughtful questions I’d ever encountered. And of course, the most grateful and gracious teacher named Jake, who started a GoFundMe page to bring me to his school to discuss Finding Langston, a book that changed him.

The best part of the visit was the way that day changed me too. Students asked questions about the book of course, but we also discussed questions the book raised: racism , loss, insecurity, grief and trauma. I cried and I think Jake did too. Because my goodness, this is what happens when an inspired teacher gets ahold of a book he loves and spreads that love to students he loves and respects. As tired as I was, I left energized, remembering that you can never know how one story can impact a reader. Or how books can change them.

When I returned home, I wrote Jake telling him what the visit meant to me and I thanked him for his work in bringing me to his school. And he sent me this—a song he composed and performed, inspired by Finding Langston, which he gave me permission to share here. Take a listen and you tell me if teachers and books and the power of story aren’t the most wonderful things in the world.

Dear Diary

I have been writing stories since I was ten years old and my mom gave me my very own diary, complete with a lock and key (which I suppose didn’t offer any real measure of security given that any kitchen scissors could have rendered the fastener useless). However, sharing a room with an older sister and no real privacy, it made me feel as if I had a way to finally keep something of my very own private.

My diary was the first place where I wrote uncensored, free from a teacher’s grade, a friend’s judgment. It was the place where I practiced my writing.

Since then, I have always kept a journal, writing daily gratitude, observations on motherhood, marriage, and the highs and lows of life, writing and otherwise. Journaling, as it is now called, has become a hobby for some. But for me, it has helped to strengthen me both emotionally and creatively. It is still the place where I am my most unfiltered and it prepares me for the writing in the other areas of my life that do require other eyes, an editing pen, judgment from reviewers and readers.

With each passing year, practicing writing in my diary strengthened my writing and eventually helped me to write the papers for my AP English classes in high school and my college essays. It helped me to earn internships with magazines, write articles for professional journals, and even helped to launch my own blog, Writerhood: Thoughts on Writing, Motherhood and Everything in Between…”, and then it helped me to launch a 30-year writing career, writing about the lives of so many like journalist Ethel Payne, pitcher Satchel Paige, jazz musicians Louis Armstrong and Benny Goodman and historic heroes Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass in over twenty picture books and creating historic fictional narratives for my Finding Langston series and YA novel For Lamb.

But I certainly never imagined it would help me decades later to write the life story of the woman who gave me that diary, my mother. When she passed just weeks ago, my brother and sister assumed, as the designated family storyteller/memory keeper/writer, it would be me, who would write my mother’s eulogy and memorialize her in words during her funeral service. But highlighting the stories of others, those from history and polishing your own credentials is a long way from telling the beautiful and emotional fullness of your mother and how her life breathed life into yours.

But I thought back to my diary. To our early trips to the Malden Public Library. To all the ways my mother believed in me and my writing from the very first time she could see my love of story, books and words, and I sat down and wrote that. And I thought about each and every paper, school newspaper paper article, essay and manuscript I read to her in its earliest stages, and each time I lovingly autographed one of my books with her name or dedicated to her and each time she told me, “Lesa, I think this one is the best things you’ve ever written.” And I thought back to all the times she came to watch my four children when I needed a break or had a deadline or a speaking engagement, ensuring my career would get off the ground. And I thought too about all the times I could see her pride in me. And some combination of all those things made it into what I wrote of her and me and our time together and I hoped that somehow, some way, everyone who attended her service and read of her could see that the gift of my mother was her gift of being just the mother I needed by giving me that diary years ago and with it a legacy of love and her implicit belief that I would one day become all that I dreamed, a writer.

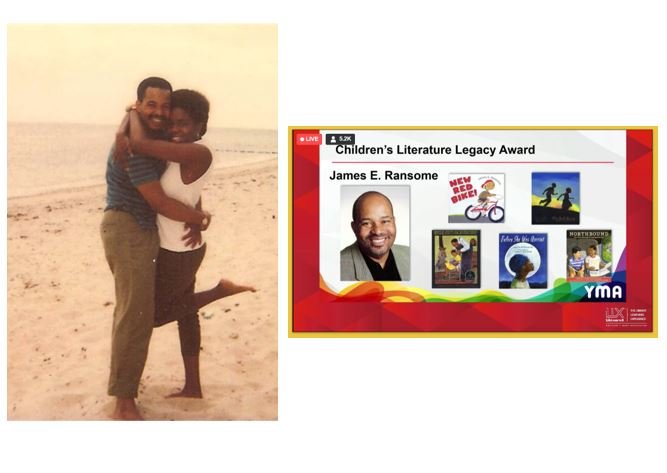

Just Rewards in Maine

We were lost. Driving down back roads and unfamiliar streets in a small town in Maine when my cell phone rang just as my GPS was issuing a direction. I cursed but answered the call coming from an unfamiliar cell, out of habit mainly. Not many have my cell number, so when it rings I answer out of fear, caution, curiosity and some combination of all.

The woman’s voice on the other end asked kindly, “Can I speak to James Ransome?” She was mistakenly given my number instead of his, we quickly realized so I put my phone on speaker and James, who was driving, aimlessly GPS-less now, chimed in.

“Hello, this is James…”

“James, we are calling from the ALA Youth Media Awards Committee…”

The rest, as they say, is a blur.

We continued now following blindly down road after road, knowing we were becoming more hopelessly lost with each passing minute the caller spoke but thoughts of reaching our destination were now the furthest thing from our minds.

“We are so happy to tell you that you are this year’s winner of the Children’s Literature Legacy Award…” We screamed. I cried. And when the call ended, we both asked each other, What. Just. Happened?

I went to the Youth Media Awards site and read aloud the description… “... honors an author or illustrator whose books, published in the United States, have made, over a period of years, a substantial and lasting contribution to children's literature through books that demonstrate integrity and respect for all children's lives and experiences…”

And then I read the list of previous recipients “…Tomie DePaolo, Eric Carle, E.B. White, Mildred Taylor, Jerry Pinkney, Dr. Seuss?”

And I cried some more. I thought back to James in college at Pratt Institutein Brooklyn, New York. When we first began dating during our sophomore year, he was the only one I knew who spent more hours in his dorm room working on assignments than going to parties. When we graduated, he worked weekends only so that his weekdays could be spent dropping off his portfolio to art directors, until finally, gratefully, he got one assignment, and then another. And one day, an art director invited him for a chat. It was Richard Jackson of Orchard Books who took a chance and offered a newbie illustrator a shot at illustrating his very first picture book entitled Do Like Kyla, written by Angela Johnson. Thirty-three years later, and Do Like Kyla is still in print. He illustrated five more books before he felt confident enough to leave his part-time job and become a full-time illustrator. He worked seven days a week, a schedule he still keeps.

Other books immediately followed, some awards followed those. But more importantly than any number, any award, was the way he viewed the work of visual storytelling. The art of telling stories for young readers. His illustrations captured the beauty, humanity of black life from the distant past to the present. You could see yourself, your family, heart and soul, in his work.

We found our way to our destination and our waiting hosts in Maine nearly thirty minutes late, breathless and overwhelmed and still floating from the news. The next day when the awards were officially announced, James had a chance to experience the real time joy all over again. For me, I feel like I have been his co-navigator in much of his journey, watching him get lost, and found again, continuing happily on his way to destinations unknown.

A Year in the Life

It’s been a year. And looking back on the goals I set out for myself, I am saddened to read that many have fallen short.

On the corkboard above my desk where I often post reference photos and materials for works in progress, I decided this year to also post, what I hoped would be a guiding principle that forced me to focus on being present rather than mired in past mistakes, hurts and disappointments. The guide post reads, “Last year I Survived, but this year I want to Live.“

2022 was a year where I managed to do much of what I had in the past: Getting through. There were more health concerns, less exercise than I would have liked, more slogging through day to day in a perpetual state of to-do lists, my days centered around my calendar.

When am I going to start having fun? I’d often ask myself when another weekend rolled around and I was again sitting at my desk. Or I had turned down another invitation because of a deadline. Or I agreed to go to an event and spent much of the time worrying about, you guessed it--work. Fun and being present never made it onto my calendar.

This week, as my adult children began trickling home for the holidays, we gathered in the kitchen catching up. When my daughter Maya remarked on the contact photos I had chosen for each of them on my phone, we all began sharing our favorite photos of each other. I had chosen a wide mouthed smile of Maya on a girls vacay in Tulum, Mexico; a sweet, romantic one of my eldest daughter Jaime and her partner Zakh; my youngest Leila after her very surprising and newly pierced septum, and my son’s studious and hopeful senior thesis photo.

We showed pics of the dogs Miles and Nola, we loved, gone now, but never, ever forgotten; of our favorite family gatherings. We groaned over earlier pre-invisalign, bad hair and fashion decision versions of ourselves.

But then, Leila showed me her all-time favorite picture of me. It was 2021, shortly before I was set to host a weekend birthday bash for my husband James’ 60th birthday party. Based on the time stamp, out-of-town guests were en route, I was juggling cooking, transportation issues, housecleaning, and coordinating final DJ, bartender details for the next evening’s dance party. And yet, all that I wanted this one particular afternoon was to have a good time. To finally put away work and my stupid calendar and enjoy the act of celebration with family and friends. So, apparently, I set an intention and I set my timer. On my phone, at 3:30 pm for the alarm label, I wrote, “Fun Lesa/Whatever Happens, happens.” When the timer rang, I vowed I would have fun and let everything else go. I would finally be present and show up in the way I wanted to each and every year in the goals I set for myself. And from what I can recall the world did not collapse. I remember having one of the best weekends of my life where I thought of little else but connection and engagement with my guests. I was actually present and having fun. Fun Lesa.

2023 I know will be filled with life’s usual bumps, hardships and unexpected pitfalls. My main goal this year will be this: Instead of posting an inspirational mantra, I will post on my board my daughter’s favorite picture of me revealing the two very real, very distinct aspects of me. One, a person who needs to plan every moment of every day. The other, a person craving the need to let go and embrace life. But unlike an affirmation, I am hoping this photo will serve as a daily reminder the importance of goal setting and planning should always include setting time and intention aside for fun and the freedom of letting go and letting be and most importantly letting life, and not a calendar, lead the way.

In Search of Joy

I am listening now to Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights, a yearlong mediation of daily essays written from one birthday to his next. Gay embarked on a journey to express his joy on the delights that surrounded him--a praying mantis, nicknames, the beauty of nature and human connection, and writing by hand-- in his work as a poet, a black man while living and teaching writing in Indiana.

Each essay is more delightful than the last. And in the listening, I could not could not help but to compose my own Book of Delights. Wonder aloud at the beauty that seeps into each day in the midst of a sometimes ugly world. I write this during the bleakest of political seasons, just days from the midterm election. I often wonder how much lower the discourse will go, how much further we will divide, how much more hate we can withstand, before we fall off of the proverbial cliff. And then I listen to Gay’s essays on delights. About a praying mantis, nicknames, the beauty of nature, human connection, and writing by hand, and I wonder if my vision of the world is skewed by my doom scrolling and attention to negative political news cycles. How did I not notice the breathtaking beauty today of the just past peak leaves? The postal clerk who put free stamps on my letters when I left mine at home? An invitation to a waterfront retreat with writer friends? The warmth of a cup of tea in my hands while looking out of my office window? Standing in field of prairie grass.

Engaging in the delights is as critical as actively engaging in the very real threats to democracy. Both, I’ve learned, are crucial to our wellbeing.

Travel Writer

Travel is a large part of my writing work life. I often pack my bags and laptop to travel to small towns, big cities and every place in between to meet with school kids and teachers, librarians, aspiring writers, parents and booksellers. Leaving behind the confines of my home office provides much-needed connection and opportunity to discuss the how’s and why’s of research, and writing.

But travel is also my inspiration. A chance to grow my work, or more importantly, to incubate ideas for new stories.

Two forthcoming books, Of Walden Pond: Henry David Thoreau and Frederic Tudor and the Pond Between, and my debut Young Adult novel, For Lamb, are the recipients of putting miles between me and my desk.

Several summers ago, I made a visit to Montgomery, Alabama and the Legacy Museum and Memorial (or what some call the lynching museum) and I read name after name of the victims posted there. But what most surprised me was the number of female victims of lynching. Very rarely were these women accused of any crime. They were simply the mothers, sisters, wives and daughters of black men who were the targets of mob violence.

And that’s when I knew I had to not only bear witness to this period of history, but I needed to honor the lives of these women in story. I discovered the name Lamb Whittle among a list of female victims, with no other identifying information. I had no idea of her age, where she lived, the circumstances surrounding her death, and so I imagined what her life was and could have been in For Lamb, the story of an interracial friendship between two 16-year old girls in the Jim Crow south when one choice ensnares both families in the grip of racial violence.

Visiting Concord’s Walden Pond in Massachusetts provided the backdrop for Of Walden Pond, the source of inspiration for the dueling visions of essayist Henry David Thoreau, and Boston’s Ice King, Frederic Tudor and the ways in which Walden Pond was a bounty for both.

Henry David Thoreau once said, “The question is not what you look at, but what you see.”

For me, that is much easier done when I get out from behind my desk, meet people, see the world and find the stories within them.

A Literature Legacy

Source Booksellers owner, Janet Webster Jones and daughter., Detroit, MI

Growing up, there were no bookstores in my town, and so, it was in the stacks of the Malden Public Library where I first discovered books. I tagged along each week when my mother visited the library weighted down with armloads of books she was either returning or picking up. Shelves of titles towered over me and all could think was, one day I’m going to read every single book in here.

The library was my second home. A place that was inviting and welcomed me to explore its every inch. Being among books is my comfort, my greatest joy. I have stacks in each room in my house. While others pare down, I pile on, enjoying the promise of what those stacks offer: the downtime to savor; the discovery of a new topic or author; much needed workday diversions; brilliant inspirations of beautifully constructed characters and stories; the answers to all of my burning research questions. Often, as I rush out of my door, off to the airport, to one event or another, I can grab whatever is at the top of one of my many book piles to accompany me on my travels. But, even when I arrive at my destination, I still often seek out a local bookseller to visit.

When I return home to MA for visits, it is Frugal Bookstore in Roxbury, Porter Square Books in Somerville and Eight Cousins in Falmouth; In New York City it’s Books of Wonder and Word Bookstore; Politics and Prose in Washington D.C.; Source Booksellers in Detroit; EyeSeeMe in St. Louis, MO; Anderson’s and SemiColon in Chicago, Let’s Play Bookstore in PA. Of course, back at home, it’s my hometown hero, Oblong Books, a treasure in the center of town, where owner Suzanna Hermans has created a haven for the writing community with author talks, book launches and virtual events. Whether or not I’ve named them here, each indie bookstore is serving a vital need in their communities.

Though some of these brick-and-mortar indies couldn’t survive the big box and online giants, those that remain continue to do the work of shoring up communities. Each time a bookseller is lost, it is a loss for a community as well because booksellers aren’t simply selling titles, they are giving life to neighborhoods and serving the needs of diverse communities. In many instances, they are the new community centers, performance spaces, gathering spots, work centers, play group stops, launching pads, employers. Booksellers are reimagining the way we are experiencing and expanding our interactions with the written word.

This month, NAIBA, the North Atlantic Independent Booksellers Association honored me with the 2022 NAIBA Legacy Award for my contribution to children’s literature. The incredible journey to this incredible honor began among the stacks of towering titles, begging me to read, to explore and of course, to write. Thank you NAIBA, libraries, and all of the Indie booksellers across the country who continue to feed our reading and writing lives.

Transitions

Transition is the word I most hate seeing in the editorial notes I receive

from my editor during the revision process. Straddling the in-between and

finding a way to seamlessly bridge narrative scenes is where it seems I

most need to develop my skills as a writer.

But transitions, I’ve discovered, are difficult for many writers. Which makes

sense, because outside of the publishing world, transitions on every level

are challenging. Over the past several weeks, I’ve worked on many

transitions of my own.

Several years ago I transitioned from writing picture books to writing middle

grade novels, and now I have completed my very first YA novel, entitled

For Lamb, which will release in 2023. (Look for an upcoming ARC

giveaway coming soon!)

Last month I watched as my youngest daughter transitioned from a college

student at Emory University into her first job offer and moved into her very

first apartment.

But the most challenging transition this year was watching my dear, sweet

foster dog fail Miles Morales, who was as active and energetic as a puppy,

begin to decline. He’d received a bladder cancer diagnosis the month

after I’d signed his adoption papers. It was terminal, the vet informed me,

but Miles seemed determined to defy the three-month prognosis he was

given.

When I first met Miles, he had spent much of his nine years in the shelter

system. He’d been used as a bait puppy, his teeth were intentionally

ground down, I suppose so he couldn’t defend himself against dogs who

were attacking him. Yet, when I arrived at the shelter in 2021, he looked at

me with sheer, unblemished trust.

Perhaps it was because he had spent so much time indoors in shelters for

much of his life, but he loved the outdoors. He begged to spend long hours

outside, often dragging me along as he happily trotted on miles long walks.

He loved basking in the sun, exploring the woods beyond our home,

sniffing flowers, napping in the grass. His all-time favorite activity was

burying bones and toys in hiding spots that he would later unearth and

move to “safer,” more secure locations, away from our prying eyes.

He arrived in winter but when the weather warmed, I put his water bowl out

on the deck where he’d hydrate after a busy spell of one of the

aforementioned activities. Each morning when I woke, I filled my tea kettle

and replenished his outdoor water bowl to ready us both for our busy days

ahead.

But then, as his cancer spread, and my once active Miles slowed to a halt, I

had to make a difficult decision. Last week, Miles transitioned just as I

imagine he would have loved. In a field of grass, under the shade of a tree,

with family by his side.

Transitions are hard. But they are also a necessary part of writing, moving

forward, moving on, and can be a beautiful stage in straddling the lives we

lived and what lies beyond.

#blackwomengivelife

Co-presenters: Vanessa Brantley-Newton, Shadra Strickland, Tracey Baptiste, me, and KWE co-director Crystal Allen

That is the hashtag I used in a recent Instagram post I shared by fellow

author and co-presenter Tracey Baptiste after our time at the much

heralded Kindling Words East writing retreat in Massachusetts.

I had filled half of my suitcase with books and thought what I needed was

the time to read and collect my thoughts in between my speaking

sessions. Perhaps too I could find time for chitchat with my peers, whom

I’d been disconnected from throughout the pandemic years, at the bar and

our meals. If I could squeeze in a walk, I’d count the weekend as a win.

But when I arrived I saw several authors I’d only met only online. These

were black authors. Black women authors, whose work I’d read and

admired. And the conversations began.

Between sessions, our fearless organizer, Crystal Allen gathered each one

us together--Janae, Shadra, Vanessa, Daria, Eileen, Lisa, Kekla, Oge,

Tameka, Christine--as a group and then we gathered more, on our own, in

small clusters, in pairs, at dinner, breakfast, at the bar, the lobby, sipping

tea, wherever, whenever, we could

My research books were forgotten as conversations were started and the

laughter never seemed to end. I thought I needed solitude, but it turns out I

needed a community of black women who understood the very unique

issues we face in the world of publishing and beyond. And just when I

needed them most, there they were, providing me with much needed

advice, support, friendship and laughter. Some of them, I’d known through

conferences, others only through their books, but there we were together,

sisters of the heart, rekindled at Kindling Words.

A Clearing in the Woods

When a friend invited me to a writing retreat in the woods of Pennsylvania at the

Highlights Foundation, I had more reasons than fingers for why I couldn’t join her:

my schedule, the dog, my deadlines...But those were the exact reasons why I

needed to leave home for the quiet of the woods.

I filled a large suitcase, 1 tote bag, a Sonos speaker ( I cannot live without my

music), and a cooler and I was off, not quite guilt free, but happily on my way. I

prayed I wouldn’t spend the entire time catching up on sleep, or the news, so I

immediately laid out the research books I needed to tackle for my upcoming new

project. I arranged myself by the window, put on my slippers, poured a cup of tea

and I was off. The quiet of the day cleared my head and while I stared out of the

window at the woods beyond and the ideas that seemed so impossibly far away

at my own home desk, now flowed easily onto page after scribbled page. I read

for hours. I started each day with meditative writing. I stretched. I journaled

before going to sleep. I wrote two speeches I’d been putting off. And I tore

through the research I’d been struggling with.

It could have been the three deliciously prepared meals served each day that

were not planned, shopped for or prepared by me. It could have been the limited

wi-fi. Perhaps it was the absence of a television, stove, washer/dryer and

vacuum, and all of the other domestic responsibilities disproportionately placed

on women that drain us of our creative resources. Now, instead of writing and

working during the in-between times, my day in my own private cabin, was all my

own.

When it came time to leave, I was ready. My time away revealed what I suspect I

already knew. That not enough time was spent on feeding my creative self. I had

at least a ride home to contemplate the many ways I would need to carve out at

home, if not a clearing in the woods, a clearing of my own to find the space to

think and write and create. At least until I can get away again to another cabin in

the woos…

Black History Month?

Each year, well intentioned educators and librarians curate Black History Month book lists intended to provide young readers and parents with a wide array of titles to diversify their collections and, I imagine, to allow non-black readers the opportunity to read stories that center on the experiences of black subjects. For one month out of the year. I certainly believe that Carter G. Woodson had it right in 1926 when he conceived of Negro History Week as a way to educate people about black culture and history. It was a time when educating the general public about the contributions of black Americans in the face of gross misrepresentation and underrepresentation was sorely needed and it provided a powerful counternarrative. Yet increasingly, when I see these lists released each February, I grow concerned and I wonder, Where are the titles featuring people of color the other eleven months of the year?

At what point are books featuring powerful, instrumental figures like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Satchel Paige, Major Taylor, Katherine Johnson, Louis Armstrong, Ethel Payne and Claudette Colvin part of our collective history? And not just the names we see in history books but the millions of black citizens who defined and shaped this country through the vast contributions they made by building, working, fighting for this country since its inception.

"There is no American history without African American history," says Sara Clarke Kaplan, executive director of the Antiracist Research & Policy Center at American University in Washington, D.C. The Black experience, she said, is embedded in "everything we think of as 'American history.' "

It is important that in homes and classrooms across the country we remember black stories, black figures, black heroes, black scientists, artists, athletes, activists, journalists, politicians, citizens during Black History Month. But we best honor them, young readers and the honest and complete history of this country by continuing to do so every other month of the year as well.

Word of the Year

Just this week, The New York Times published an article in their Wellness Newsletter entitled, What’s your Word of the Year: To get the most out of 2022, try choosing a word that can help you make thoughtful decisions and nudge you toward positive change. The article encouraged thoughtful exercises and guidelines for selecting a word to serve as your focus for the upcoming year. But for years my dear friend Jeanne and I have been utilizing this practice in the days leading up to each new year. “...Have you chosen your word…” one of us would text the other, and a conversation would begin on our reflections of the year we were leaving behind along with our hopes for the year ahead. In the past, I have chosen the words, Habits, Slow Down and the all important, No. This year, I chose the word Love.

After a convergence of political, health and social crises in 2021 left me feeling depleted, I decided to nurture, uplift and seek out inspiration by showing up more presently each day of 2022 in Love for my family, my friends, my community, my work and myself. So here’s to 2022, a new year, new words and of course, Love.

Everybody Knows your Name

I live in a wonderful community a couple of hundred miles north of New York City. It is a small town that often reminds me of the town where I grew up in Malden, Massachusetts. A place where, like the sitcom Cheers theme song, everybody knows your name, as in strangers and friends alike happily greet you when they see you on the street. Often when I visit my local library to pick up research books I’ve ordered online, between the time I park my car and the time I reach the front desk, my books are waiting with a smile and sometimes questions about my next project.

A couple of years ago, I realized I needed a different type of community. Spending hours in isolation each day at my desk left me craving the companionship of others who create in this beautiful, yet often insane, world of publishing. I knew I needed someone, anyone to commiserate with and so I reached out to several local writers I knew and one spring afternoon, I made a pot of chili, some cornbread, everyone brought a dish, and we gathered around my dining room table and talked about what a writer’s group could look like. Some wanted to focus on critique. Others on the business side of writing. Some a combination of the two. But all of us were sure that community is what we wanted. And that’s how we began.

Since that spring day two years ago, we have continued, every six weeks, travelling miles to each other’s homes, virtually when the pandemic hit. Three members left us, two others moved away, a few more have joined. What has remained is a steadfast group that has nourished me with their encouragement, advice and friendship and helped my work to grow.

Over the past 18 months, four of us watched our books grow and evolve into something we could be proud of. As release day neared, we celebrated and discussed our plans and our fears in our group like expectant moms in a doctor’s waiting room.

Check out the new releases welcomed onto shelves from some of the members of my incredible Writer’s group.

Bank Street Best Books of 2021

Cheers for Being Clem, included in The Best Children’s Books of 2021 by Bank Street Books. Fans of Finding Langston and Leaving Lymon will love this third and final companion in the Finding Langston trilogy centering on the life of Clem Thurber Junior as he navigates fear, friendship and his many questions about what it is to be a man in 1946 Chicago when you can’t seem to live up to legacy of a hero father who died in the war.

★ "In addition to exploring Clem’s relationships with his friends, Cline-Ransome offers unusually perceptive portrayals of his family members, their interactions, and their strong, ongoing, but largely unspoken grief. Clem’s engaging first-person story, written with simplicity and emotional clarity, provides a rewarding conclusion to this historical fiction trilogy."—Booklist, Starred Review