The Brutal Truth

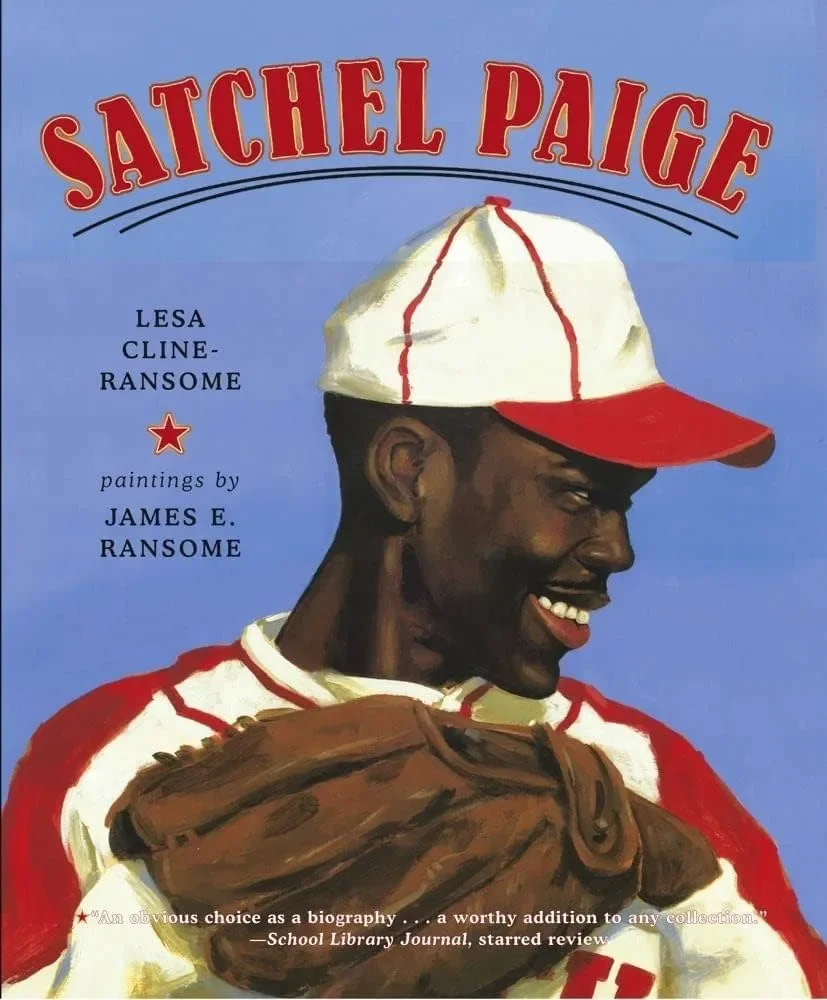

I began my writing career by publishing a picture book biography of the Negro League pitcher Satchel Paige. He was an iconic figure who brought to baseball a unique blend of sportsmanship and showmanship. In a team sport, he was a loner, forgoing the team bus to drive alone in his own car to games on the road. Some games, he wouldn’t bother to show up at all. Instead of sharing the spotlight, he sought out the limelight. Asked his age, he gave interviewers various ages that spanned nearly twenty years. His own autobiography provided a fictional birth date.

As a new writer, I struggled to find a way to balance the complexity of a man so talented in one area in his life, but so personally flawed in others. Satchel Paige was called larger than life, a character, a storyteller, but he wasn’t often called what he was—a man who also lied. I worried, Is this something that I can tell young readers?

Just last month, I completed my first long-form nonfiction biography that extended well past one deadline and several more. I spent too much time fussing over pre-writing strategies I’d never fussed over in my pantser past—what the structure should be, how many chapters it would have, chapter headings. I wasn’t sure exactly how to tell the story of a woman whose life couldn’t be confined within chapters, headlines and outlines.

Ida B. Wells was a journalist, activist, suffragist and anti-lynching crusader. She was born in 1862 six months before the Emancipation Proclamation, just shy of freedom. She and her five younger siblings were educated at a Freedman’s Bureau school in her hometown of Holly Springs, Mississippi. Her mother Lizzie attended school with her children, hoping that learning to read and write would help her to correspond with newspapers as she sought to reunite with family members that were sold off during enslavement.

As a young girl, I had seen the name Ida B. Wells among the many black history heroes listed in the Jet and Ebony magazines that were a mainstay in my home. But I came to understand the impact of her legacy most fully through research for my first young adult novel, For Lamb.

For Lamb explores a secret interracial friendship between two teenage girls in the Jim Crow South and the deadly consequences of their actions. Much of my research focused on the female victims of lynching. Ida B. Wells’ The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States became one of my most valued resources as I looked at the numbers of black people lynched following Reconstruction and throughout the decades that followed. It was in no small part, due to Ida’s advocacy and spotlight, through her endless investigations, editorials, speeches, boycotts, and demands for justice that political leaders, newspapers, that the nation finally began to pay attention to the atrocities being committed on its black citizens.

“The way to right wrongs is to shine the light of truth upon them,” Ida once wrote, and shine the truth she did. In her early thirties, she was the first black woman to own a national newspaper. And the editorials she wrote for the Memphis Free Speech sparked fury among the city’s white citizens.

“Nobody in this section believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men assault white women…” she wrote in an 1892 editorial entitled “The Brutal Truth.” Several days after its publication, while Ida was visiting New York, the Free Speech offices were destroyed. A white mob stood stationed at the train depot awaiting her return intent on killing her.

Ida B. Wells —Original: Mary Garrity Restored by Adam Cuerden

But it would take more than the destruction of a printing press to silence Ida. She didn’t return to Memphis but she did continue to publish her scathing editorials lambasting cowardly politicians, religious leaders and a two tiered justice system—one for whites that included a fair trial and one for blacks that needed only an accusation to render judgement by a lynch mob.

Unlike Satchel Paige, Ida was a teammate to her entire race. She spent much of her life embattled, questioned at every turn for the decisions she made. Sometimes with those in her own race who felt she was too outspoken; sometimes with other women activists who questioned her dedication to the cause when she married and became a mother. She waged war with Frances Willard, the white Christian Temperance president and longtime abolitionist who, in an interview, blamed the lynching of black men on their drinking and illicit behavior. She called out the white press for their biased reporting, allowing their headlines to scream out unfounded accusations that offered cover for mob behavior. Although she was just over five feet tall and petite, she physically fought off a white train conductor and male passengers who attempted to remove her to a 2nd class smoking car when she’d bought a first class ticket. She refused to acquiesce to the will of white suffrage organizers at the 1913 first National Women’s Suffrage Parade who told her to march at the back in a section designated for black suffragists to appease their southern white contingent. Ida stayed put and marched with her own Illinois delegation, the only black woman walking proudly at the front.

What version of the truth do we owe our readers?

Her life’s work it seemed was fighting, but essentially Ida was fighting the lies that sought to define and justify the harming of black people. “Black people are more sinned against than sinning,” she once wrote, and she needed the world to know it.

The facts she uncovered revealed that while black literacy rates soared, black businesses opened, black land ownership increased, so too did the rates of lynching of black citizens. The reasons given for lynching were predicated on a lie—that lynching was used as a tool in the protection of white women from the sexual assault by black men. And here was Ida, with the truth in hand dispelling that narrative with facts and figures. The year her Red Record was published, accusations of rape or attempted rape accounted for a mere forty-seven of the one hundred and ninety-seven reasons provided for the lynchings that took place in 1893. If rape was the cause, what then could account for the number of black women being lynched, Ida asked.

At a time in our world when the truth feels optional, when lies are repeated as easily as breathing, when the people who spout them suffer little consequence personally or professionally and can even be elevated to the highest office in the land, as writers, what is our obligation to the truth? What version of the truth do we owe our readers?

Over the span of thirty books and twenty picture book biography subjects, and in the years and missed deadlines it has taken me to absorb the life, work and legacy of Ida, what I have learned is that my obligation is to offer an honest accounting of a life or “The brutal truth,” as Ida described it.

The world of nonfiction is a world of truth telling. But how much is too much is a question I have been grappling with since I first sat down to write Satchel Paige.

When I think of Ida and her battles and her steadfast grip on honesty, I looked at anti-lynching resolutions passed in state after state. The victims she memorialized by giving them voices and names. And I thought of a country that was finally forced to face its own shame through the hard honest work of Ida and others—Frederick Douglass, Mamie Till, the NAACP—and it was only then the lynching slowed to a stop.

We are entering a moment when honesty about real life experiences, history, and injustice can come at a cost, especially for writers in marginalized communities in the form of censorship and banning. And just maybe we can’t all be as brave as Ida, or morally courageous as the heroes we read and write about, but don’t we owe it to ourselves and our readers to at least try?

In community,

Lesa

My forthcoming book, "Ida B. Wells: The Untold Truth of a Country" releases September 2026 (Holiday House)