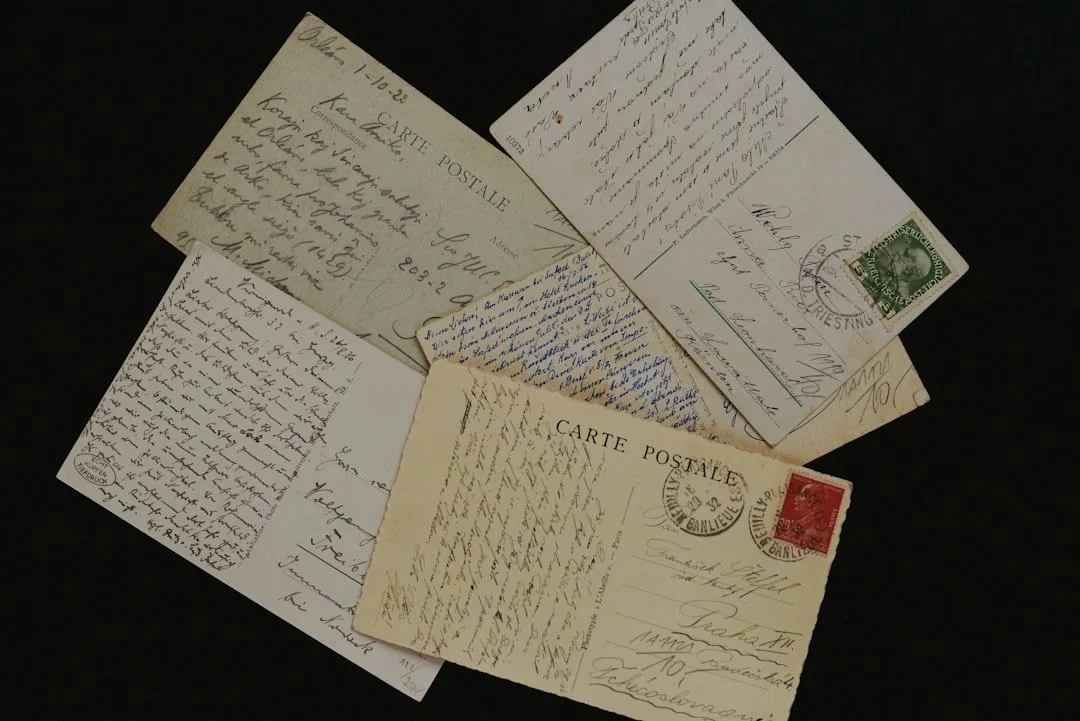

Letters from Home

Photo by rc.xyz NFT gallery on Unsplash

Dear Lesa,…

The letter from my mother arrived as it always did, to my dormitory mailbox at 200 Willoughby Avenue in Brooklyn, New York. I had been aching to live in New York ever since middle school and the series Welcome Back Kotter aired on tv and Saturday Night Fever hit theaters. The grit, and lack of pretense of New Yorkers spoke to me. I imagined that I’d be gloriously at home surrounded by tenement buildings, graffiti and Brooklyn accents stronger than my Boston one.

But when my parents drove away from the Pratt Institute parking lot, I realized I already missed home. Missed it so much that I called my parents three times a day from the lobby payphone.

Within my mother’s weekly letters were pieces of home—the daily errands she ran, what she and my father ate for dinner. Nothing revelatory, but I’d save them in piles in my drawer and reread them as needed, when I was at my most homesick, feeling as if I’d lost my moorings.

I have begun again to write letters at a time when manual writing is becoming obsolete. Elementary schools have ceased teaching what was once a staple of my grade school curriculum—penmanship and cursive writing. Who needs penmanship when we no longer write by hand?

Teachers bemoan the fact that their students can no longer decipher the cursive writing in documents like the Declaration of Independence, let alone sign their own names.

When my siblings and I recently sold our family home after the death of my mother, it required us to do the much put off task of clearing out the house. We trekked upstairs to a stifling attic where boxes and crates, ancient issues of Ebony, Jet, and Boxing magazines were piled. My brother discovered his first toy chest, I grabbed albums from my father’s vinyl collection. And then, as we turned to head downstairs for a break my brother said,

“Lesa, you’ll want this.”

It was a diary. My mother’s 5-Year Diary from 1942-1947. She was sixteen years old when her diary entries began and in those pages, I traced her life living in Everett, Massachusetts with her parents Anne and Elbert Sneed, and her four younger siblings, twins Elbert and Elvera, Lewis and Shirley (her youngest sister Ruby had not yet been born.) and several children that my grandparents raised as their own.

January 3, 1942: There was house cleaning today and plenty of baths. I got a letter from Raleigh (her uncle) and a picture from Dalton Smith.

I never knew my mother kept a diary. But maybe I should have guessed it. She was a woman who kept secrets close and respected the privacy of others. When I was 10 years old, I returned home from school to discover that my mother had bought me my own diary, complete with lock and key. The cover was a blue floral pattern and inside I quickly inscribed my name in my once neat handwriting under the lines “This Diary belongs to…”.

I shared a room with my seven-years-older sister Linda. In our room, nothing was completely mine. She decorated, decided when we slept (after she finished her late-night phone chats and playing loud music). She spread her cosmetics and fragrances across “her” dresser. But the diary my mother gave me was all mine.

Long after my diary writing ceased and I left for college, the diary lay untouched, hiding in the bottom of the dresser I’d claimed when my sister left for college. I don’t know where the diary has since disappeared to. Most likely it was among the many attic items I wasn’t able to rescue. But I remember how important that diary was to my private and writing life. I finally had a place to vent my frustrations and insecurities to craft stories from my childhood adventures with friends. I could yell at my sister without actually yelling at my sister.

My mother’s diary involves no yelling. She documents her teenaged life in a manner that was so starkly different from my own—dance lessons in her living room, ice skating, bowling, church choir practice and reading. I wondered when and where she had time to write her private thoughts in a home filled with family.

When I read the entries in her signature handwriting, I am reminded of her letters from home and the cards she sent for every birthday, every holiday, every heartache.

April 23, 1942: I went to see Count Basie and Maxine Sullivan tonight…

Some argue that communicating electronically is the new shorthand. But what of the distinction of handwriting, the idiosyncratic flourishes that are part of written correspondence? While we text and email and post on social media with regularity, nearly sixty-four percent of the population report that they will never write a letter by hand.

Historically letter and diary writing has been the realm of many white men and wealthy white women. There are only four published diary accounts of black women from the 19th century—journalist Ida B. Wells, educator Charlotte Forten Grimke, poet Alice Dunbar Nelson, and seamstress Emilie Davis.

Alice Dunbar Nelson — Unknown Photographer

Research for so many of my historical nonfiction and fictional narratives involve digging through primary sources to extract the vital stories of my subjects but there are far fewer primary source documents and photographic evidence from people of color. They continue to be left out of history. The lives of black people were rich and diverse and complex, and yet, too many of their stories have been written and narrated by others.

I often wonder how much harder researching will become when so much of our correspondence is relegated to the digital world? When our handwritten letters, notes and diaries disappear from our archives.

My once uniform print has evolved into scraggly, barely legible markings, but I have returned to letter writing because what I know is that no text message could ever replace the intimacy of the written word. My handwriting and the ways I which I communicate with paper and pen are my own indelible imprint. From the stationery to the fold of the paper, to the color of the ink, those elements become part of the message.

Our writing need not rival those of Martin Luther King’s letters from a Birmingham jail or Thoreau’s journal meditations on the natural world. Quotidian writing holds every bit as much relevance in documenting the truth of our lives.

Write a letter. Send a postcard. Make notes in a journal. Sharpen your pencil and know that in writing with your own hand you are preserving the story and the history of you.

In community,

Lesa